Analysis and Results

The purpose of the study was to discover through the exploration of lived experiences, the influence of noncognitive factors on college student's academic preparedness. Chapter 4 includes a discussion of the study results and data analysis. The results and data analysis are presented using raw data collected from 16 participants to describe the influence of noncognitive factors on student's academic preparedness.

Textual Categories

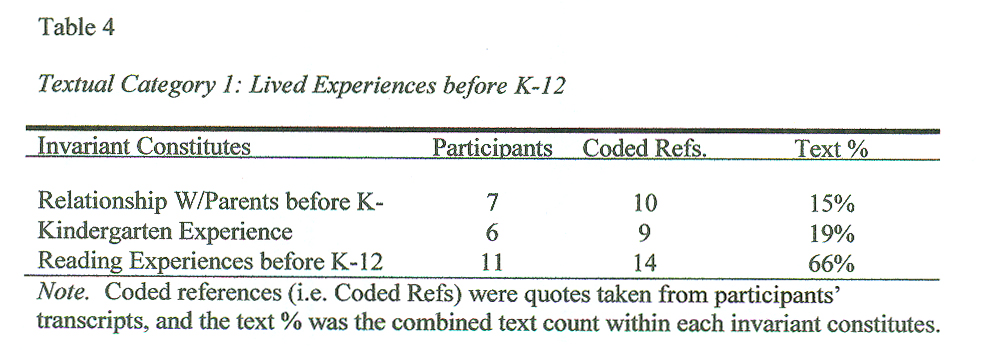

To avoid bias, participant's textual descriptions (i.e., significant statements) provided a substantial portion of the narrative descriptions. Table 4 illustrates the first textual category, lived experiences before k-12. In this study, tables merely provided a visual representation of participant's significant statements within each textual category.

Textual Category 1: Lived Experience Before K-12

As seen in Table 4, a substantial portion of participants remembered someone reading to them before they entered elementary school. Several exemplar quotes for the textual category are presented below to understand what the participants experienced.

Phil stated, “Yes, my mother always read to me.” However, David noted “I know when I was really young, before kindergarten, my sister used to read to me every night from a certain series of books.” Tanya responded,

I was read to quite a bit by my older siblings. I remember my, uh, sister having certain projects that she would go over, and I would be snoopy and curious. And she would tell me what she was doing. I remember her doing reports, like, on the Salem Witch Trials or her reading The Hobbit to me, things like that. So probably more advanced reading than for a preschooler you’d – I would say.

As indicated by these statements, although some participants were read to by their mother, most participants were read to by their siblings or someone else, which may suggest a lack of parental involvement. Of the eight participants with two-parent families, five participants were read to before entering elementary school. Six of eight participants from broken families were read to as children before entering elementary school. In this study, the majority of participants were read to as children before elementary school and whether they came from broken homes or two-parent families did not matter. However, the data results concerning early educational factors before elementary school were not definitive with regard to participant's academic preparedness because the level of interactive responses between parent and child was not accessible. The next subsection introduces the textual category lived experiences during k-12.

Textual Category 2: Lived Experience During K-12

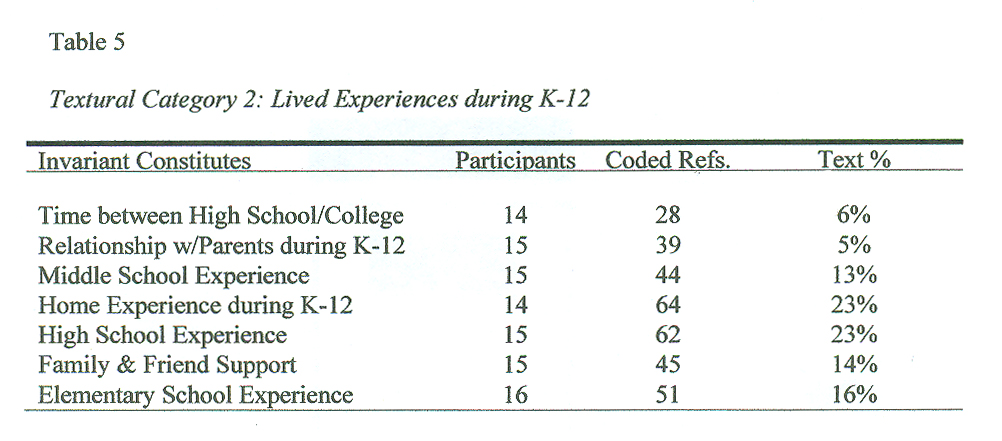

Table 5 illustrates the participant's shared experiences within the textual category lived experiences during k-12.

Serena noted “I was with my godparents since I was one and my brother since he was two.” Josephine stated “My mom and my father were divorced. I had a stepfather, which my in home wasn’t all that great, because there was a little bit of abuse but it wasn’t a lot.” Rachel reported “my, growing up in my house was very dysfunctional. Um, it was not an easy, to go home to.”

The common experience was broken families and alcohol use by either the participant or a parent. However, the common implicit experience was the lack of guidance, the lack of academic encouragement, and bad choices made by participants during k-12. As examples, Serena acknowledged “we weren’t guided very well and were making a lot of mistakes.” When asked how home-life was during k-12, Lydia indicated “Sort of difficult because my mom and my dad were going through a divorce and we were going back and forth between – I had to live with my grandparents.” Laura also noted,

That was a nightmare for me because things at home were bad, and nobody helped me with work, and I never understood it and the teachers did not care to help. So I just don’t – now I see that I could understand it, but back then, no, there was no one at all to help me understand.

These negative examples of lived experiences were common within invariant constitute home experience during k-12. Most participants, whether coming to college directly from high school or returning to school as an adult, reported negative family circumstances, which may suggest a lack of encouragement leading to procrastination and lack of effort. For instance, James, a high school adult, noted “my father was an alcoholic, so he was never around…my mom worked two jobs…she didn’t have time to like sit there and help me with homework.” David reported “I think a lot of people my age, uh, have problems with procrastination… and so I guess that would probably be one of my hindrances.” Rachel wished “I wish I would have had somebody to, to push me or encourage me.”

According to James, family issues affected his attitude and motivation to achieve academically until he met his girlfriend in his senior year of high school. In his own words James noted,

I wanted to achieve more because while I was in high school and stuff, be – all the way up to my junior year, I didn’t see myself going to college. I didn’t see myself actually passing. I got very, very lucky every single year, actually, up until my senior year, because I barely passed.

James further noted “as soon as my senior came and I met my girlfriend, my attitude changed drastically. And I actually felt like I wanted to achieve more, and actually go to college.” In brief, James is an example of how one individual can influence students’ behavioral choices, attitude, and motivation.

The shared experience within the second textual category was that drinking alcohol, lack of guidance, and participants’ unfortunate choices potentially contributed toward their becoming academically underprepared during k-12. These negative experiences were common regardless of whether the participant entered directly into college from high school or was a returning adult. By searching deeper into the transcripts and overlapping the invariant constitutes, the only discernible difference between these students was that eight participants had two-parent families during k-12 and the other eight participants were from broken homes. From the two-parent families, five participants (i.e., John, Frank, Tanya, Henry, and Phil) reported relatively few negative experiences in their homes or k-12 schools, which suggest some positive influence on their behavioral choices.

Textual Category 3: Lived Experience During College

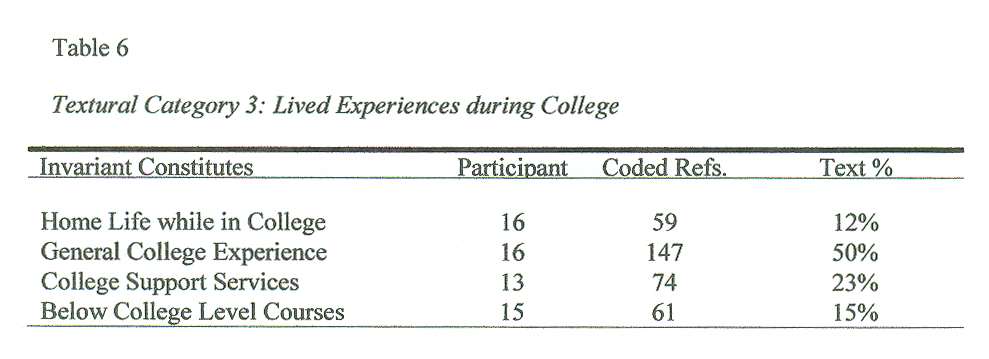

Table 6 shows textual category 3, which was about participant's lived experiences during college and several exemplar quotes from this category were helpful toward understanding the phenomenon of academic underpreparedness.

Frank, a returning adult, noted “…it was a culture shock because I was actually on my own and got to make decisions and that’s why I never finished, because I made some wrong choices in my life.” The wrong choices Frank discussed were 2 years after his initial entrance into a university when he started drinking alcohol and eventually dropped out of college. However, Frank had no academic underpreparedness issues or negative family issues during his k-12 experience. The data suggested that even with a stable two-parent family and no academic issues during k-12, if a personal issue develops during college, academic underpreparedness issues may also develop.

Another of Frank’s personal issues was that his instructors used a different teaching method from the teaching method Frank had during his k-12 experience. The university atmosphere was impersonal consisting of mainly lectures and classroom with hundreds of students. Frank reported,

Like in my Psychology class there was over 200 of us in there, and the only way you got anything out of it was to network through your friends, and I was an introvert at that time, so I did not have the personality to talk to people or the self confidence to do that at that time.

Frank also reported “It was like you were in a factory. There were tons and tons of you being pushed through to get your degree and I just didn’t learn very much.”

Frank began to drink alcohol and eventually dropped out of school, and he did not return to college for over 20 years until enrolling at Northern New Mexico College (NNMC). Frank revealed,

When I first went to college, the last year that I attended in ’91, it started as a weekend thing and then it went on to almost an every night thing. I couldn’t study without having a beer or I couldn’t do anything or be with friends because the only friends I knew drank, so it was hard for me to associate college and not drinking.

Frank’s personal issues with drinking and the teaching methods at the university may have compounded as negative influences on Frank’s lived experience during college, which may have influenced his academic underpreparedness.

Frank’s whole persona transformed after coming back to school; he is no longer an introvert and he has stopped drinking alcohol. Frank reported,

I’m also president of a student organization here on campus, so we help each other out that way by talking and keeping ourselves busy for my part, so that way I don’t want to start drinking again, so that’s what helped me so far.

Frank added “I’m more outgoing and outspoken and I have self confidence and that is one thing I would always tell a young college student, is to make sure you get your self confidence and know what you can do.”

Tanya was another example of coming from a two-parent family and experiencing few negative issues during k-12. She tested out of high school at 16 years of age and went to college and received an associate’s degree directly afterwards. However, she did not return to receive a bachelor’s degree until 14 years later and she developed some personal issues. More specifically, Tanya developed a physical disability, married an alcoholic, and had children, which created scheduling issues. Tanya’s compounding personal issues with 14 years away from college negatively influenced her academic preparedness.

Phil was another participant with a two-parent family. He did well in k-12 even with a learning disability, apparently because of family support and the high school accommodating his disability with appropriate teaching methods. However, the university he attended directly after high school did not accommodate his learning disability with a teaching method conducive to his learning style. The result was that Phil dropped out of the university and started going to NNMC where his needs were met.

The results indicated that participants from two-parent families, who also do well in k-12, may develop a variety of personal issues that negatively influence their academic preparedness during college. Participants such as Frank, Tanya, and Phil encountered negative experiences after k-12 that influenced their academic underpreparedness. However, these three participants and the other participants reported largely positive experiences during college at NNMC, mostly because of college support services.

The second largest qualitative invariant constitute within textual category 3 was college support services. NNMC combined below college level courses with college level courses as part of college support services. Phil noted,

Link courses are you take two different classes. They are supposed to – link is – I’m taking English and a biology course. So the English – our first semester is Basic English. We write our essays. The second semester we move to a different book that has essays in science. Then in biology, our papers have to be in MLA format like English. So that’s how it’s supposed to work together. Both teachers talk to each other. Its two days a week right after each other.

In another example about linked courses, Henry noted,

That’s a really good class because they help me; well they help us a lot with everything. They explain us how we have to do it, how we do it, and the teachers are really good. They always helping out, I was like for me like, I don’t speak really good English. They put me like in the writing center, so I have to go, and it really helps me a lot.

In brief, the data suggested the majority of participants believe college support services were a positive aspect of their academic preparedness.

As a summary of the first three textual categories, the first textual category suggested a possible lack of parental involvement in the lives of most participants. The second textual category reflects participants’ negative experiences at home and at school during their k-12 lived experiences. However, within the third textual category, some participants had negative experiences at the start of their college experience and positive college experiences as a result of college support services at NNMC. During the interviews, participants revealed their growth in maturity, the ability to make better decisions, and a change in motivation for obtaining a college degree. An example of this was James, as he reported “I was becoming more mature and actually sitting there and actually learning things.”

James was a very interesting interviewee, as he revealed a surprising form of data that was not initially recognized as important. James revealed “…I actually finally and actually had somebody to impress in school because no one really actually did care how I did in school, so.” The perception that no one cares along with a previous statement from Rachel that she wished someone had pushed or encouraged her to perform well academically was implicit within the data. The data was implicit because the reasons for academic underpreparedness may not always have obvious implications for participants’ behavioral choices.

Textual Category 4: Noncognitive Factors

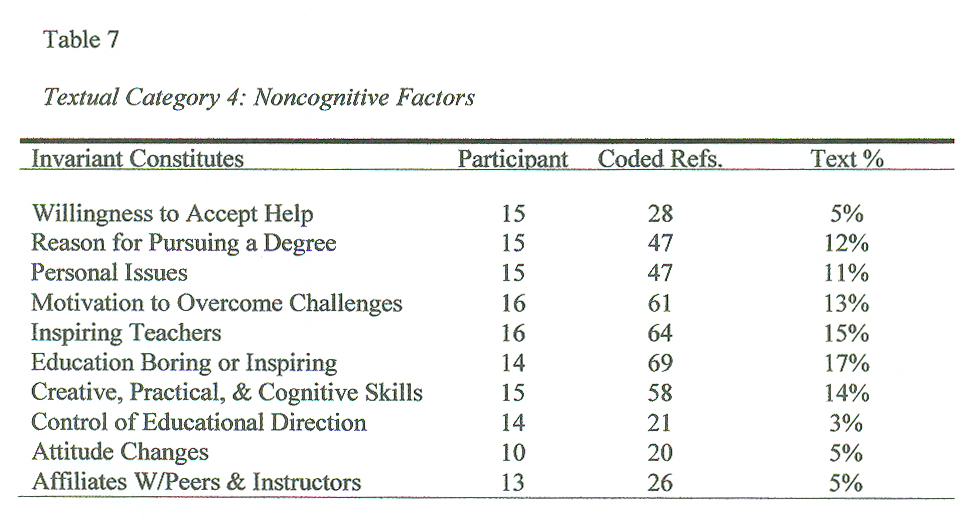

Table 7 lists invariant constitutes concerning a variety of noncognitive factors within the textual category. Several exemplar quotes from this category were helpful in understanding participants’ lived experiences. Rachel noted,

I think it’s very important for, for teachers to, to teach education wise but also to keep in mind that uh it’s important to give life skills, so that students will be able to compete in the real world. Um, and I think that that should be important to, for the teachers to remember that a lot of the students that, that are high risk, will have the challenge of having to learn skills and life skills.

Frank noted a story about his teacher in high school,

He had a little calculator that played musical notes and we used to play the song La Bamba. Well I took his calculator and I played La Bamba for him on the calculator just from listening to the notes…it was the math, because notes are like math, steps in math, and that’s how I figured it out.

Participants wanted a combination of practical, creative, and cognitive skills to make education fun and provide a balance of life skills.

If we don’t have an imagination, how could we write? How could we deal with life if we don’t have any creating or any imagination or nothing to be proud of because I created that and I was part of creating that.

Delores added “I think being creative is very important. I think it helps the cognitive skills along, whereas if you just have the cognitive without the creation, then it doesn’t come together.”

Most participants found some courses stimulating but they also believed that something was missing. Using Rachel as an example of an adult returning to school, she acknowledged that some courses were fun because these courses allowed students to work together. She acknowledged “one of the things that I do like is when the teachers allow other students to work together and um, and that helps a lot of the stress and anxiety that the students go, go through.” Rachel added that she wanted to obtain a sense of self-esteem by completing a college degree. However, the most important aspect she noted was “I think that it’s important for teachers to inspire their students, to figure out a way for our students to stay in school.”

For the invariant constitute inspiring teachers, most of the participants remembered teachers creating positive educational results by inspiring them to learn. Frank noted “My sixth grade teacher, he was awesome. He always inspired me to be myself and encouraged me to go further in education.” Serena replied,

Because she was strict in the way we did our writing, but yet made it fun, I think that more people were willing to – especially the younger ones – were more willing to participate and try harder. Read out lout. Probably kids that wouldn’t do it in high school were doing it in her class. She was my favorite teacher and I would take another course just to take another course with her.

Josephine responded “My mathematics teacher inspired me. He was one tough – he taught us what we need to know to go into college, and he pushed us to learn it.”

The data suggested that a tough teacher may become inspiring to the class if the students achieve positive educational results. Other participants experienced an inspiring teacher. Serena noted “Something that they’re actually going to use, it can be very inspiring.” Serena further remarked “there are some people that just walk into a room and you know it’s going to be fun or inspiring.” Josephine remarked “my mathematics teacher inspired me.” Phil added “my 5th grade and my 7th grade substitute science teachers. Those two were awesome.”

The results also suggested that these participants had a high level of motivation and perseverance. The invariant constitute motivation to overcome challenges included a large amount of data in which participants discussed college support services positively. As an example, Rachel indicated,

I’m on financial aid so without those, without the ability with financial aid I would have never been able to go… Sometimes it takes me longer to understand. But, I, but, uh, so I am determined to, to finish this education, even if it takes me longer than the 4 years that they have.

In another example, Jane explained “I have set my mind to finish up what I started… I’m up till all hours trying to study.”

An unexpected result was the mention of having fun during education. Apollo noted his early school experience as fun, and Serena noted, “There’s some people that just walk into a room and you know it’s going to be fun or inspiring.” When asked about high school, Lydia replied “Fun, because I was in all regular classes, I got good grades and I was in sports.” When asked about middle school, Frank replied “It was interesting and it was fun and good.” The question was not asked about fun in education; however, participants mentioned the topic of fun many times, which may suggest a level of significance for students who are academically underprepared for college.

Another unexpected finding was in relation to self-regulation (i.e., control of thoughts, attention, and actions) and metacognitive skills (i.e., an ability to plan for the future). John was a good example of making good behavioral choices, complying with rules, and planning for the future. Although John lived in a dangerous neighborhood with drug dealers and with murders taking place, he never joined a gang or got into trouble. He eventually planned a successful business.

The data extrapolated from John’s significant statements suggested that family activities with parents may counteract negative neighborhood influences. John may have obtained self-regulation and metacognitive skills from his family activities with each of his parents. For instance, when questioned about his mother, John responded “She was always cooking and we always joined in – my sister and I… My sister and I would always take turns, you wash dishes, and I’ll dry up.” When questioned about his father, John responded “he started a business selling vacuum cleaners, so I drove everywhere.” Life skills from family activities may provide self-regulation and metacognitive skills to improve students’ academic preparedness.

Structural Themes

Giorgi (1985) considered themes as aspects of a complex phenomenon transformed into a structure of events. Giorgi also noted meaning units used for structural themes are not found grammatically within text but in perceptions of what is relevant to the phenomenon. By using imagination, the structure of the phenomenon can illuminate a new understanding but only through participant's significant statements, which becomes the phenomenological reduction of describing experience as presented by those living the phenomenon (Giorgi, 1985). A table within each subsection provided a visual illustration of structural themes discovered using invariant constitutes and research sub-questions.

Structural themes emerging from research sub-question 1

The first research sub-question was: how do academically underprepared college students perceive their college lived experience? The analysis of this research sub-question began by first asking the participants to “tell me about the experiences, good or bad in college, you have had during your education.” College experiences were a positive explicit experience for most participants.

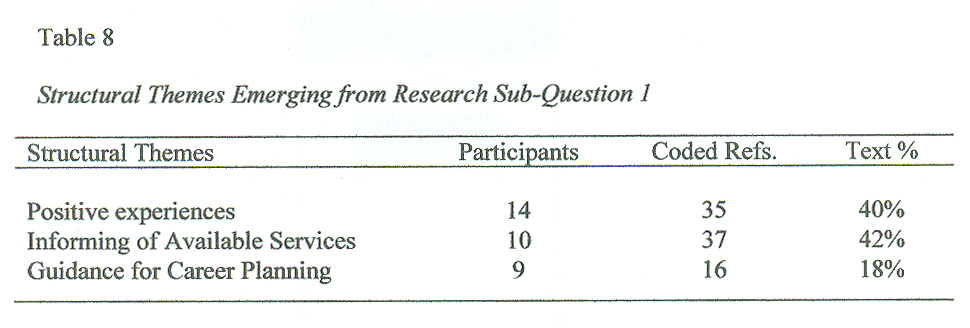

However, those positive experiences did not provide a complete understanding of the structure of events. Using probing questions and imagination, participant's descriptions revealed an implicit structure of their college experience at NNMC. This implicit structure is illustrated in Table 8 as informing of available services and guidance for career planning.

Most participants reported having good experiences during college with relatively few bad experiences. However, most participants learned about the availability of college support services through other students or instructors, rather than from the admissions counter. Serena noted “I can be honest with you, most of the programs here, I have found out from other students.” Serena also noted “I had absolutely no idea what I was doing, but they seem to say things like, we’re not here to hold your hand or that should be common sense.” In addition, Delores reported “I didn’t – don’t remember ever getting anything from them.”

Some participants had special needs because of a learning disability and they reported obtaining information immediately during admissions. For instance, Phil reported “yes, because the first person I talked to was the lady of special needs. She was the one that set my courses. She’s my advisor for now.” Nevertheless under further probing about how he found out about services, Phil explained “My mother found out. One of our neighbors used to work here. So she told her who to go to. Then we set an appointment with her. Then I met her, and I came here.”

In reference to guidance for career planning, the link courses include orientation and motivation sessions during the summer, which encourages students to plan for the future. For example, John acknowledged,

There was a lot of motivation during those courses. During that summer we were always talking about future this, future that. We did speeches. We talked among ourselves. We had little support groups within our own classes, and we thought what are you going to do? Where are you going from this? What do you want to do?

However, most participants, even the students in the link course, did not know about this opportunity. As an example, Phil stated “I haven’t seen – I haven’t seen yet. But the program I’m in right now, they are very supportive, because it’s – I’m in the linked courses.” Also in reference to guidance for career planning, Tanya stated “I don’t really recall anything right now… information access is definitely an issue on the campus.”

To answer the research sub-question of: how do academically underprepared college students perceive their college experience? Most participants had a positive experience at NNMC. However under probing, participants revealed that receiving information about available services was not obtained through the admissions counter when they initially enrolled at NNMC. Participants also revealed that guidance for career planning was a limited activity; most participants did not receive this service. Although most participants reported a positive experience at the college, under probing, participants explained that providing information about available services and guidance for career planning were not part of admissions staff duties.

Structural themes emerging from research sub-question 2

The second research sub-question was: how do academically underprepared college students perceive their lived experience related to early educational factors before and during k-12? During the interview, participants were asked to “describe any experience you have had with someone reading to you as a child, or if no recollection, describe your k-12 experience.”

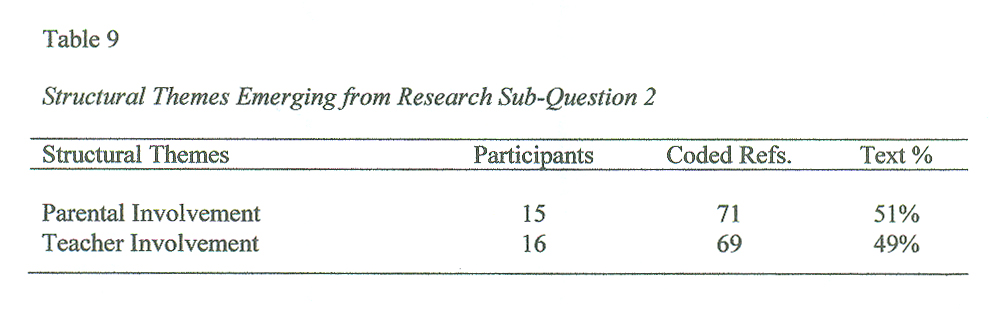

The exploration into this research sub-question suggested structural themes such as parental involvement and teacher involvement as the underlying structure.

In reference to teacher involvement, Rachel reported “Um, without their support and their understanding I probably would have never made it an effort to um, you know, there, to um, learn the way I did.” Also, Josephine reported “This is when I was in high school. I had a teacher – my English teacher, and she motivated me to write, write, and write.” However, these instances of teacher involvement were sporadic and most participants’ experiences were negative concerning k-12. For instance, Delores explained “K-12 you pretty much sat there, be quiet and it was almost like they were drilling something into you rather than letting you show the willingness of wanting to learn.” Laura reported “Junior High as it was – as it was called back then was really hard because there was no one at school who really wanted to take the time to help me, and at home there was nobody.”

In reference to teacher involvement, Rachel reported “Um, without their support and their understanding I probably would have never made it an effort to um, you know, there, to um, learn the way I did.” Also, Josephine reported “This is when I was in high school. I had a teacher – my English teacher, and she motivated me to write, write, and write.” However, these instances of teacher involvement were sporadic and most participants’ experiences were negative concerning k-12. For instance, Delores explained “K-12 you pretty much sat there, be quiet and it was almost like they were drilling something into you rather than letting you show the willingness of wanting to learn.” Laura reported “Junior High as it was – as it was called back then was really hard because there was no one at school who really wanted to take the time to help me, and at home there was nobody.”

I don't think I was that happy all through those years. I was, but I think – well home life had a lot to do with it, so I think I was just living, like I was alive, and I was going through school doing the motions of school.

I don't think I was that happy all through those years. I was, but I think – well home life had a lot to do with it, so I think I was just living, like I was alive, and I was going through school doing the motions of school.

Also within the structural theme of parental involvement was the important influence of having at least one parent who encouraged participants to achieve academically, which was contingent on a friendly or hostile atmosphere within the home. For instance, Lydia was one of the two participants from broken families who had an encouraging mother supporting her both financially and emotionally to achieve academically during college. Lydia reported her parents stopped fighting and her mother was available emotionally and financially for her during college. In another example, Delores and Laura were both from two-parent families; however, they both experienced much confusion and fighting between their parents, which suggested a lack of emotional support or encouragement to achieve academically.

Structural themes emerging from research sub-question 3

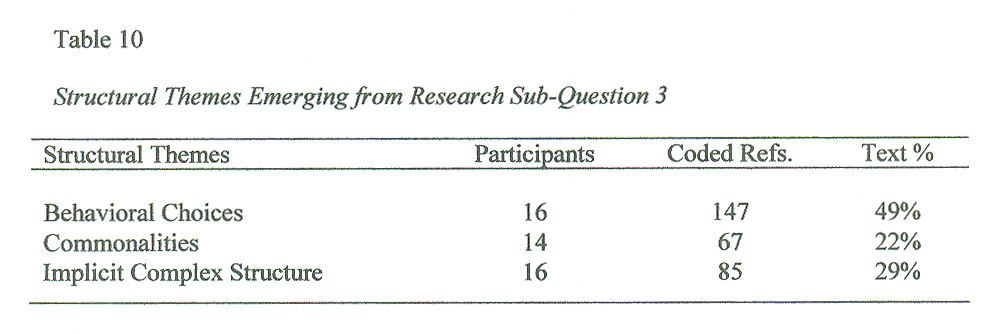

The third research sub-question was: how do academically underprepared students in college describe lived experience related to personal factors that may help or hinder their educational experiences? Participants were asked to “describe a personal issue that may help or hinder your ability to obtain a college degree.” Table 10 includes the structural themes emerging from the third research sub-question followed by examples from participant’s significant statements.

In reference to commonalities, Jackie noted her biggest issue toward obtaining a degree was “financial aid probably ’cause my mom doesn’t work right now. She’s on disability and stuff and my father, um, are currently unemployed.” Also, some participants did not have a place to live. Laura explained “I needed somewhere to live, and I was willing to live in the park, and come over here during the day, you know leave my dog outside parked, you know tied up so that I could go.” Apollo reported “I was like, homeless for, like, about a month. I had to stay in my girlfriend’s car because I didn’t have anywhere to stay; I had no money at the time.”

The data suggested an implicit complex structure within reported commonalities through a reflective discovery of participant’s circumstance from iterative readings of invariant constitutes. Although she was from a two-parent family, Jane reported family health issues in her home and as the oldest child she often in cared for her mother. Jane noted “I had to play second mother because either my mom was sick or she was giving birth.” She dropped out of school in the tenth grade because of family issues, which may have led to her academic underpreparedness.

Delores explicated “Um, my high school years were not pleasant. I dropped out cause I was – I was not happy and I wasn’t learning anything in school cause I – I just hated getting up and going to school.” Josephine noted “What I love about my dad is, even though he drinks a lot, he’s always around…I was kind of like a trouble maker.” Rachel reported “I wish they would have stressed to me more of the uh, taking it more of accountability and responsibility…it would have made it easier for me to stay in school.” Rachel also reported “I never had parents or adults to follow through on my education.” Further, these significant statements may indicate an implicit complex structure of influences on participant’s behavioral choices.

For instance, Frank was also from a two-parent family and reported no negative family issues. Nonetheless, he had a personal issue in which he developed a drinking problem during his first 2 years at a university. Frank noted “I couldn’t study without having a beer or I couldn’t do anything or be with friends because the only friends I knew drank, so it was hard for me to associate college and not drinking.” Frank dropped out of the university and did not return to college for over 20 years because of his alcoholism.

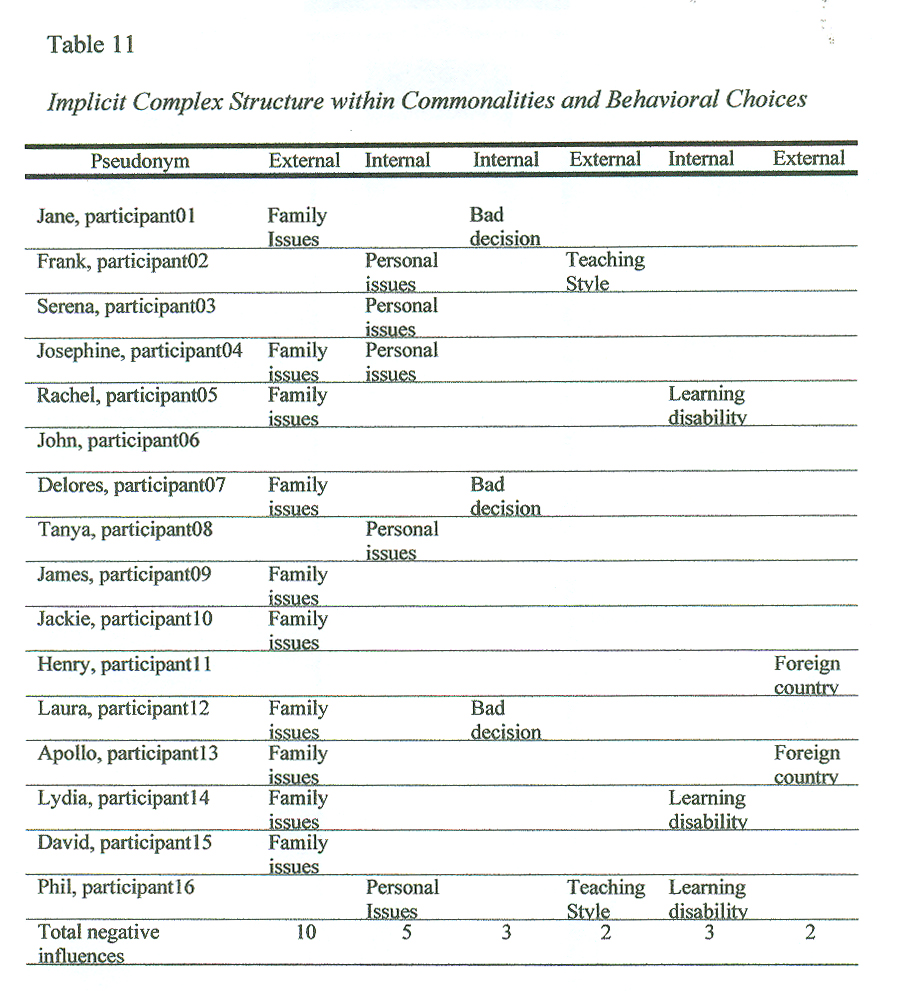

Table 11 illustrates the implicit complex structure within commonalities that may have influenced participants in their ability to control their behavioral choices as an interlocking influence on their academic underpreparedness.

To further illustrate, Serena was from a broken home in which her grandparents took care of her. Serena reported a lack of guidance throughout her k-12 experience and eventually began drinking alcohol at age 13. Serena reported “I started drinking about 13… I didn’t care back then.” Rachel added “I wish they would have stressed to me more of the uh, taking it more of accountability and responsibility… I regret the fact that I should have been in school rather than…falling through the cracks.”

Conversely, some participants reported they had supportive families in which their parents control their education, or gave them incentives for good grades, and made them do chores around the home. For instance, Henry acknowledged “my father control my education… he tells me like you going to take English… I say okay because anyway I have to go.” Phil stated,

I remember one semester my mom told me if I – I should get an – I have to have an A in all my classes to go to a concert this semester…I had an A for that whole section because I wanted to go to that concert.

John added “we were always active at home and there were a lot of chores.” In this study, these participants’ lived experience were not the norm but do support the notion of an implicit complex structure that influences academic preparedness, as these participants reported only a few negative family issues.

Structural themes emerging from research sub-question 4

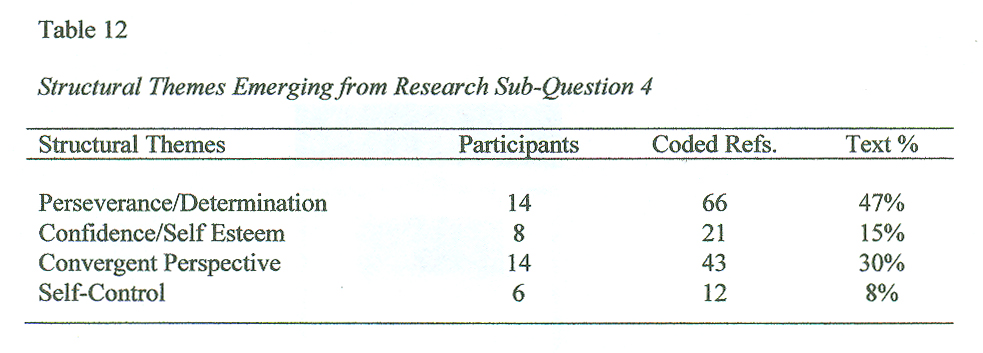

The fourth research sub-question was: in what ways do academically underprepared college students describe lived experience related to affective factors such as overcoming the challenges they face in obtaining a college degree? Participants were asked “describe how you will overcome the challenges you face in obtaining a college degree.” Illustrated in Table 12, the exploration into this research sub-question suggested structural themes such as confidence/self esteem; perseverance/determination, convergent perspective, and self- control were influential toward academic preparedness.

Concerning perseverance/determination, Jane proclaimed “I have set my mind to finish up what I started…I’m very determined…I’m up till all hours trying to study.” Serena added

Raised two children, lost one, and kept dusting myself and getting right back up… Sometimes I spend six, seven hours at the computer studying… I’m very determined to finish…I think that I’ll leave from here with a good, strong foundation, if I fight for it.

Rachel noted “I’ve had to learn through those struggles and be determined…I am determined to, to finish this education, even if it takes me longer than the 4 years. Tanya reported “I’m very resilient and adapt well… perseverance is key.”

Participants’ perseverance/determination may have had some influence on their confidence/self esteem. Frank noted “I’m more outgoing and outspoken and I have self confidence…without self confidence it will be hard to succeed in a college because you are on your own.” Rachel acknowledged “one of the things that I look on once I get my degree is my self esteem.” When completed, James added “I’ll feel good about myself.” David described his eventual degree completion as “a sense of personal fulfillment.”

College support services appeared as a convergent perspective with participants’ affective factors, as every positive sounding participant indicated receiving some form of financial aid, linked courses, or tutoring. Participants overwhelmingly indicated that they had the perseverance and motivation to overcome their academic underpreparedness. For example, Jane proclaimed “I have set my mind to finish up what I started…I’m up till all hours trying to study.” Frank provided a 5 year plan by stating,

My first step is obtaining my Associate’s, which I will get within a year, and then I’ll get my Bachelor’s 2 years later and if everything goes great, I would like to go on for my Master’s and get my CPA in Accounting.

Josephine noted “I will not let obstacles get to me, no matter what.”

These affective factors of determination and perseverance converged with college support services in helping participants to overcome having little family emotional and financial support. Rachel noted “if I wouldn’t have the ability of financial aid it would be rough.” Delores, another participant with family issues, was adamant about her college support services. Delores reported “I’m getting tutoring for my algebra, and it’s awesome.”

Additionally, three of the participants read to in their childhood were diagnosed with learning disabilities during K-12. However, Phil, a special needs student, noted “the campus here has the best – one of the best programs for special needs students.” In addition, Lydia, a special needs student, noted “I’m trying to – just because I have a disability, to me it doesn’t mean that I cannot do it. I know I can do it even with a disability.” Lydia added “with the special education person she like – she’s there for me to talk to if I need to, or help me understand what classes would be the best.” Participants’ learning disabilities did not seem to matter, as the convergent perspective of college support services, combined with their affective factors of perseverance/determination, was a positive influence affecting their confidence/self esteem.

One participant provided evidence of having knowledge of their self regulation abilities but referred to it as self control, and another participant referred to it as having control over his direction in life. For instance, David noted “there’s a certain, certain level of self-control, I guess, that I have over myself for, uh, pushing past the procrastination and getting that work done.” John added “I also was told I can change direction any time, which is true. By being told that, I was actually informed that they don’t have a direction for you. You choose that.” These statements may have significance because awareness of information about personal abilities such as choosing your own direction in life or knowledge of self-control may influence academic preparedness.

Structural themes emerging from research sub-question 5

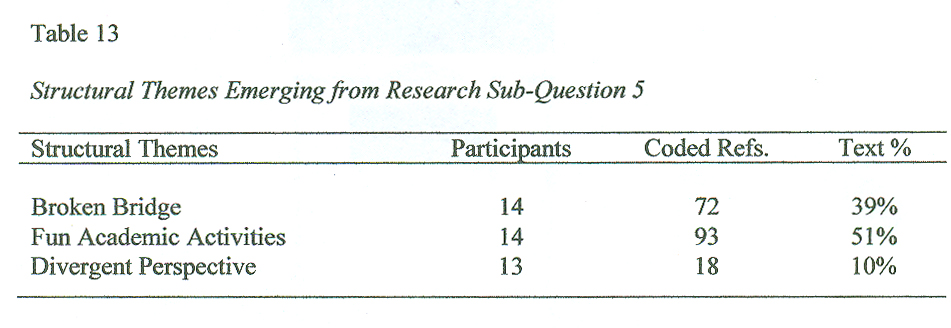

Related to Table 13, the fifth research sub-question was: what influences do creativity and practical skills have on participant's lived experience related to their academic preparedness? To explore this research sub-question, the interview question was: describe an educational situation in which a teacher inspired you to think creatively or use practical skills. The theme fun academic activities were found in textual category invariant constitutes but broken bridge was found through research sub-questions and insightful participants. The divergent perspective was the result of imaginative reflection and integrating an aspect of interpretive phenomenological analysis, which encourages commonalities, convergent perspective, and divergent perspective.

In reference to a broken bridge, participants coming into college may need to have an intrinsic reason to pursue the rigors of education and the lack of creativity in the classroom implies something important was missing in education. Delores noted, I think being creative is very important. I think it helps the cognitive skills along, whereas if you just have the cognitive without the creation, then it does not come together. Apollo provided insight,

I can count the amount of people I see inspired by learning and developing their mental capacity and it would not be that much…education is not what it should be… I think that’s where, um, uh, there’s like a bridge – a broken bridge in a sense.

Delores added “I didn’t feel there was a reason for – for what we were doing.” Rachel revealed “I think that it’s important for teachers to inspire their students, to figure out a way for our students to stay in school.”

In reference to fun academic activities, Lydia commented, “with my biology, even though it’s difficult with lecture, or it’s boring with the lecture, the lab is so much fun because it’s hands on.” Lydia noted,

My junior teacher, she like – she would give us an essay that we had to make up a story, so it made me think of my gosh, this is like so much fun, I wanna actually keep doing this because it’s enjoyable.

In another example Phil added,

the one class that does give me a way to express myself is my photography class…I have so many different ideas, like movies, music – everything in my mind. The only thing is how to get that from here into the real world.

Serena concluded “I think our English teacher was very strict, but she taught in creative, fun ways.” Serena added “probably kids that wouldn’t do it in high school were doing it in her class.”

Using a divergent perspective, it was found that most of the participants had a positive viewpoint of the importance of creative and practical skills, but at least one participant had a negative viewpoint. Frank noted “I believe you need to be well rounded in order to survive in this kind of world we live in today.” John added “Creative skills? Well, they help you and they’re very important because they actually solve problems for you – your own creativity can solve a problem.” However, on a divergent note, James replied,

Not, not necessarily because I feel like learning math, reading and all of those cognitive skills is something people really need to learn in life because they’re used almost every day. And those – the practical skills are good, good to learn, but they’re not, they’re not as important as cognitive skills …You chose if you want to know the practical skills.

The divergent perspective suggested the importance of creative and practical skills; however because they were not part of entrance assessment or part of teaching methods, these skills were not viewed as required or important to at least one participant.

Creative Synthesis of Academic Underpreparedness

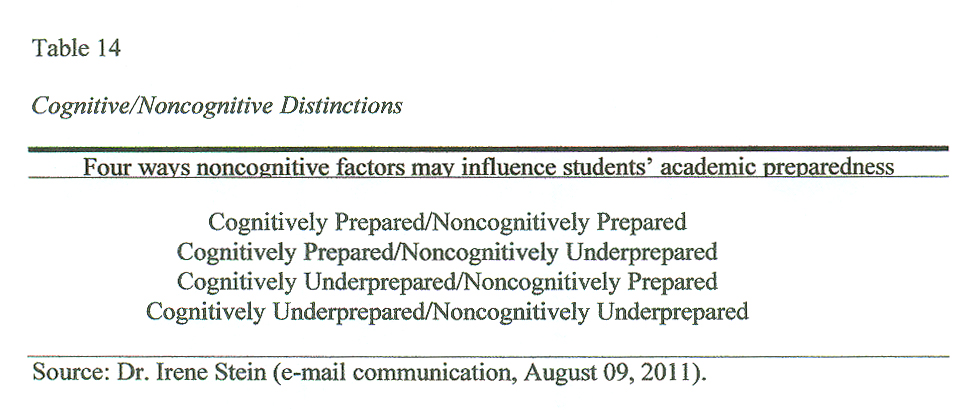

The creative synthesis was an attempt to create what Moustakas (1994) called a “culmination of the research in a creative synthesis” (p. 18) by using cognitive and noncognitive distinctions to reveal types of academic preparedness and underpreparedness. Making the design of phenomenology usable in this way provided what Pringle et al. (2011a) noted as evidence-based data firmly rooted within participants’ direct quotes about the phenomenon. Table 14 includes a summary of ways noncognitive factors may influence students’ academic preparedness and underpreparedness.

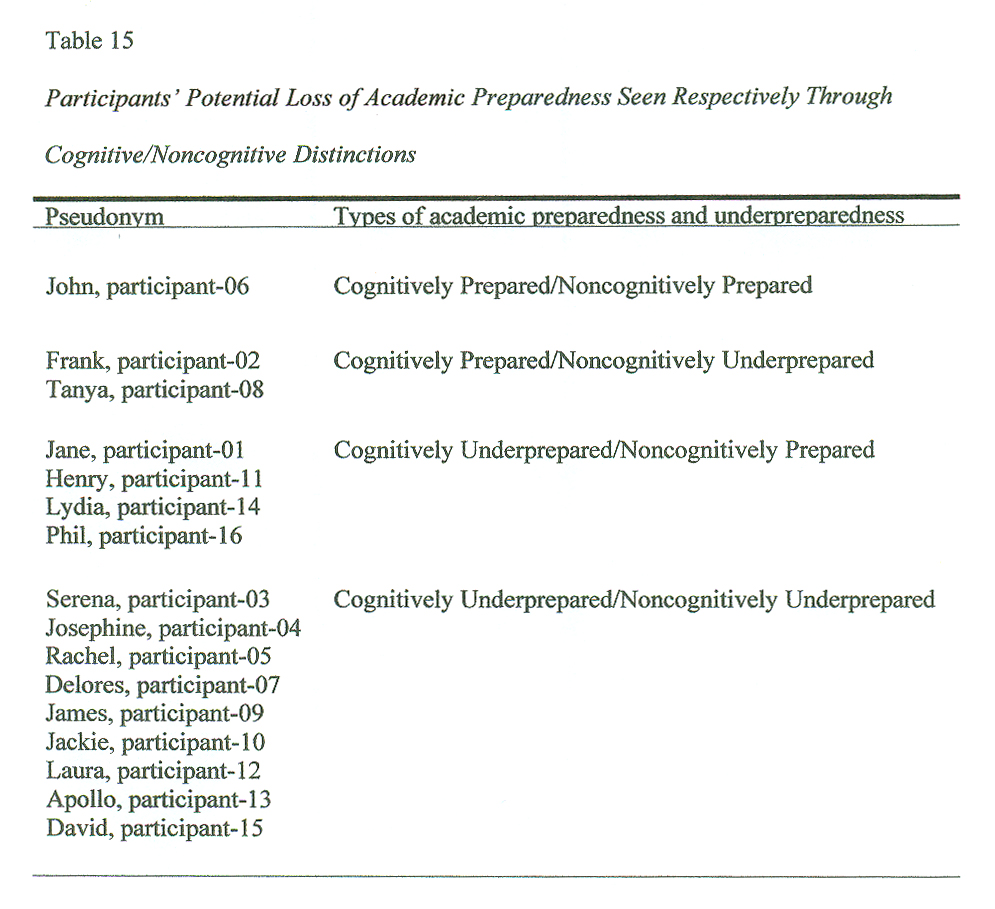

Table 15 includes the cognitive/noncognitive distinctions used to associate participants within each distinction followed with a creative synthesis concerning each distinction. The term cognitively prepared was operationalized as participant's metacognitive ability to plan (e.g., home-schooling their children, planning a business, or planning entrance into a university). The term noncognitively prepared was operationalized as participant's self-regulation ability to control their behavioral choices (i.e., control of thoughts, attention, and actions), which may result from family support. Self-regulation and metacognitive skills may provide a deeper understanding, which may help educational leadership understand how to address academic underpreparedness. This portion of the study accounted for the complexity between academic preparedness and underpreparedness.

Cognitively prepared/noncognitively prepared

The cognitively prepared/noncognitively prepared distinction implied academic preparedness in both constructs. The data results revealed that John had home-schooled his daughter and he was merely going to college and taking noncredit courses to give his daughter a sense of security. For instance, John noted “I home schooled my daughter.” In addition, John noted,

I came with her because her not being ever in a classroom was a little scary for her, and I said, “Don’t worry, I’ll go with you…even though I’ve already got my diploma and stuff, but they didn’t care so it was all right.

John was the only participant considered both cognitively and noncognitively prepared for college, which suggested he had control of his behavioral choices and his metacognitive ability to plan. As well, the next distinct revealed two other students were also cognitively prepared.

Cognitively prepared/noncognitively underprepared

In this distinction, cognitively prepared/noncognitively underprepared respectively equated to metacognitive preparedness and underprepared in self-regulation skills. In one example, Tanya (participant-08) tested out of high school at the age of 16 and obtained an AA degree soon afterward. However, 14 years later she decided to return to college for a BA degree. Tanya noted “So having to be divorced and trying to negotiate things with my youngest child is probably one of my biggest issues that’s kept me from graduating.” Tanya’s personal issue made her an at-risk student in college and qualified her as noncognitively underprepared.

In addition, Frank (participant-02) was cognitively prepared because he entered a selective university directly after graduating from high school. However, Frank had an alcohol problem and he dropped out of college. His alcohol issue suggests he was an at-risk student and therefore noncognitively underprepared. If Frank were to stay away from drinking alcohol, he could easily succeed in college because of his strong family and school affiliations. Tanya and Frank were both cognitively prepared but noncognitively underprepared, which may have lowered their ability to control their behavioral choices (i.e., control of thoughts, attention, and actions).

The three cognitively prepared students (i.e., John, Frank, and Tanya) provided leadership skills at the college. John indicated that he was providing informal tutoring for many of the participants within the link courses. Frank indicated he was the president of a student organization at the college. Tanya she belonged to an Honor Society at the college and she attended project planning meetings to help the community. These participants were metacognitively prepared.

Nonetheless, two of these participants were underprepared to self-regulate. Frank had to stay away from drinking alcohol and Tanya had a troublesome alcoholic ex-spouse and children, which presented scheduling issues. These examples contradicted the notion that self-regulation provided students with better metacognitive skills. However, the imbalances between these skills were found the most influential factor toward academic preparedness and underpreparedness.

Cognitively underprepared/noncognitively prepared

The cognitively underprepared/noncognitively prepared distinction was defined as metacognitively underprepared with self-regulation preparedness, which appears to contradict the subjective analysis for the other participants. However, while assessing participants for this distinction, it was discovered that some participants who may have been noncognitively underprepared during K-12 were noncognitively prepared during their entry into college. For instance, some participants did not have family support during k-12 but had it during college.

In Jane’s (participant-01) circumstance, the reason was because the family health issues that held her back during her k-12 experience were absent during college because her family supported her college aspirations. Jane noted “I had a real hard life. Pretty much my grade – my education really consisted from first through eighth grade…I was out of school because of family problems, health issues.” Jane initially met the criteria of cognitively underprepared for college; however because of her family support during college, she met the criteria of noncognitively prepared to deal with her academic challenges. Jane explicated “My kids would say, well, what’s holding you? Why aren’t you finishing up? I said I don’t know.”

Henry (participant-11) had strong family support from the beginning, and he was only cognitively underprepared because of not speaking English fluently. Henry noted “Like math, physics and chemistry, I’m really good at that, but the good thing here is like they prepare you for talking.” In addition, Henry noted,

The relationship, I’ve got a good relationship with my father because I realize that nobody give you better advice of your father because he have lived the life, and my mother I consider her like my best friend because we – I always talk to her about my problems.

Because of his strong family support, Henry met the criteria of noncognitively prepared to overcome his cognitive language difficulties.

Lydia (participant-14) and Phil (participant-16) both have learning disabilities; however, Lydia currently has strong family support, and Phil always had strong family support, which makes them both noncognitively prepared for college. Phil entered the university directly from high school and found the teaching style was different at the university in comparison to what he encountered in high school, and the university did not give him the disability support services he needed to perform academically. Phil reported,

In LA, it was – the lady that supposed to help you, she was so busy – so many students. She just – it was like she didn’t know who you are. I walk in. I talked to her like the day before, and she’s like, “Who are you again?”

However, because of Phil’s strong family support and the college’s support services, he met the criteria of noncognitively prepared to handle his learning disability.

Lydia was cognitively underprepared because of her not receiving the extra support needed for her learning disability during most of her K-12 experience, but that changed during high school. When asked about high school, Lydia replied “Fun, because I was in all regular classes, I got good grades and I was in sports.” Although she was from a broken home during K-12, she presently has strong family support from her mother, aunt, and uncle, which makes her noncognitively prepared to overcome her learning disability challenges. Lydia noted,

I can go talk to them because my aunt and my uncle have a college degree and have taken college classes and all of my family tells me just remember that this will be the best for you for your future.

These participants were potentially metacognitively underprepared but noncognitively prepared to self regulate their behavioral choice process. Interestingly, of the four participants in this distinction, three participants were from stable two-parent families with reported family issues in one family but the issues were health issues not family strife. The only possible common reason found for these four participants academic underpreparedness was a subpar k-12 educational system but this was questionable.

Cognitively underprepared/noncognitively underprepared

This distinction was defined as academically underprepared in both metacognitive and self-regulation skills. The only discernible difference between this group of participants and the other groups (i.e., the other three distinctions) was that 78% (7 of 9) of participants in this distinction were from broken families. When combining the three other groups into one group for data analysis purposes, only 15% (1 of 7) of participants were from a broken home. Although a two-parent family does not guarantee the cognitive or noncognitive preparedness of the participant, it does suggest an improved chance that participants may have preparedness in one of these two cognitive/noncognitive distinctions.

Most participants were underprepared in both cognitive and noncognitive distinctions, which may suggest a loss of self-regulation and metacognitive skills. Fifty six percent (9 of 16) of study participants were within the cognitively/noncognitively underprepared distinction. The researcher admitted fitting into this distinction, which may result in researchers’ personal bias. However, by using participants’ significant statements, an attempted was made to describe participants’ experiences without personal bias.

Serena (participant-03) was a high school dropout from a broken home but returned to obtain a college degree within 7 years of dropping out. Serena was cognitively underprepared because of being out of school for 7 years. She noted “I got straight into algebra and I hadn’t taken a math class in quite some time so, it was a little difficult.” She was noncognitively underprepared because of a personal issue (i.e., drinking alcohol from the age of 13 years) and she admitted to “creating my own obstacles for many years.” While Serena may have stopped drinking alcohol during college, she has very little family support, which potentially qualifies her as an at-risk student and noncognitively underprepared.

Josephine (participant-04) was a high school graduate going directly into college but she takes noncredit courses to prepare for college level coursework. She was very close to her grandfather who passed away causing a lack of motivation in her, which may have contributed to her cognitive underpreparedness. Josephine noted “I wasn’t motivated to succeed in school as much when he passed away.” In addition, she was from a broken home and the father of her daughter was alcoholic. Because of a lack of family support, she was seen as an at-risk student and noncognitively underprepared for college.

Rachel (participant-05) was a high school dropout during the 10th grade but returned to school 20 years later. She was cognitively underprepared because of the long period away from school. Incidentally, Rachel may lack self-esteem; she noted “one of the things that I look on once I get my degree is my self esteem.” In addition, Rachel insisted,

Again, um, I think it’s very important for, for teachers to, to teach education wise but also to keep in mind that uh it’s important to give life skills, so that students will be able to compete in the real world. Um, and I think that that should be important to, for the teachers to remember that a lot of the students that, that are high risk, will have the challenge of having to learn skills and life skills.

As a student with a learning disability and from a broken family, Rachel was seen as an at-risk student and therefore noncognitively underprepared for college.

Delores (participant-07) was categorized as cognitively underprepared because she was a high school dropout who returned after 19 years from school. Delores noted “It’s – um, I’m learning a lot more, I mean, whereas before I didn’t have – I didn’t feel there was a reason for – for what we were doing.” She was noncognitively underprepared because she has no family support and she has a tendency to make bad decisions. Delores noted, “I dropped out cause I was – I was not happy and I wasn’t learning anything in school cause I – I just hated getting up and going to school.”

James (participant-09) graduated from high school and he went directly into college. However, this may have been possible because of his girlfriend, as John noted,

I didn’t think I’d actually get out of high school until I met my girlfriend, and she’s an honors student, she’s, I don’t – she’s told me she’s never had a, anything but an A from seventh grade all the way to high school and she’s a senior now.

James added,

And if I ever need help with my homework or anything like that, she, she’ll help me. She’s actually in English – she’s actually in a higher – all higher classes than me and she’s still in high school. So, she’s actually a really smart girl, and she’s helped a lot.

James was from a broken family with an alcoholic father and a mother who worked two jobs. For the reasons previously stipulated, he was classified as both cognitively and noncognitively underprepared for college.

Jackie (participant-10) was from a broken family but managed to graduate from high school and go directly to college. Jackie was from a broken home with at least one abusive parent, which was the reason for her classification as noncognitively underprepared. In addition, she used many tutoring services, which was the reason for her classification as cognitively underprepared for college level coursework. However, Jackie may have experienced an inferior k-12 school system, as she noted “High school, just about the teachers, the Filipino teachers that we really couldn’t understand them, or they really wouldn’t help out.” Jackie further added “I didn’t really learn much.”

Laura (participant-12) acknowledged she needs to do better in both English and math, and she was taking noncredit courses to improve in these areas. She was classified as cognitively underprepared and noncognitively underprepared for other reasons as well. The main reason was that she has no family support and she lived in the park when starting college, she noted,

Well, I had a lot of barriers because to go to summer school I needed somewhere to live, and I was willing to live in the park, and come over here during the day, you know leave my dog outside parked, you know tied up so that I could go.

When asked about her parents, she added “They are both passed away.”

Apollo (participant-13) was a high school adult who graduated from high school and went directly into college. However, Apollo was from another country and he does not speak English fluently and therefore he was cognitively underprepared. Apollo was also from a broken family, and he was living out of his girlfriend’s car at the beginning of college. Apollo noted “I had to stay in my girlfriend’s car because I didn’t have anywhere to stay; I had no money at the time.” He was noncognitively underprepared because of this reason.

David (participant-15) was a high school dropout but obtained a general education diploma (GED) within a year and went straight into college. When asked why he was taking noncredit courses, David responded “Uh, we have a compass test here inside the school.” In addition, David responded, “I’ve taken the math course, it’s, uh, it’s a 102 Basic Algebra. My math skills have never been too strong. But having those courses helps me, uh, catch up.” Interestingly, David also noted, “Uh, I think a lot of people my age, uh, have problems with procrastination… And so I guess that would probably be one of my hindrances.”

Summary

The NVivo 8 software program was essential to query each interview transcript of particiants and storage of their significant statements. The steps for analyzing data were (a) acknowledging bias at appropriate moments, (b) developing preconfigured categories, (c) developing textual categories, (d) developing structural themes, and (e) developing a creative synthesis. In chapter 4, the textual categories for lived experiences before k-12 reflected most participants were read to before entering elementary school by a sibling or grandparent. Negative family issues were dominant within textual category lived experiences during k-12 and positive college experiences in textual category lived experiences during college mainly because of college support services. Another textual category, noncognitive factors, suggested most participants had some inspiring teachers during their educational experience but generally education was considered boring because of the teaching method of lecturing.

In chapter 4, the first set of structural themes suggested most participants were not informed of available services or provided information about guidance for career planning during their initial admission into NNMC but found out about these services through friends and teachers. Structural themes such as parental involvement and teacher involvement occurred on a limited basis for most participants. Additionally, the third set of structural themes such as commonalities, behavioral choices, and implicit complex structure were a major negative influence on participant's academic preparedness. However, structural themes such as perseverance/determination, confidence/self esteem, convergent perspective, and self-control were positive influences on participant's academic preparedness primarily because of a convergence between affective factors and student support services. The fifth set of structural themes such as broken bridge, fun academic activities, and divergent perspective were found as a broken potential but may become a positive influence through integrating creative and practical skills with cognitive skills.

The creative synthesis provided cognitive and noncognitive distinctions to understand types of academic preparedness and underpreparedness. In brief, chapter 4 included a comprehensive description of the results and data analysis using textual categories, structural themes, and a creative synthesis. Chapter 5 consists of findings from textual categories, structural theme findings as related to the research question, and findings related to the creative synthesis. Chapter 5 concludes with a discussion of the significance to leadership, research limitations, research implications, recommendations for future research, and a summary.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License

Please attribute legal copies of this work to Moire Tomas, Ed.D.

Also, some of the work(s) on this site may be separately licensed.

UMI Number: 3536193

Published by ProQuest LLC (2013)