- Home

- About

- Artist Statement

- Artist Resume

- History of Kinetic Fine Art

- Educational Services

- Artist Portfolio

- New Artwork

Kinetic Fine Art:

finest selection in

kinetic paintings

Phone: 505-927-7052

kinetic_art@moiretomas.com

side view of front projection and rear projection behind wall

of one type of kinetic painting

Web Development by

Moire Tomas, Ed.D

A Phenomenological Study:

The Influence of Noncognitive Factors

on Academically Unprepared College Students

Introduction

The United States community colleges do not consider noncognitive factors when assessing students’ academic preparedness (Boylan, 2009). Lindqvist and Vestman (2011) suggested noncognitive factors are characteristics such as emotional stability, social skills, and persistence. Heckman (2008) noted policy discussions in the U.S. often underrate the relevance of noncognitive factors. Moreover, noncognitive factors added with cognitive factors can increase the assessment accuracy of students’ academic preparedness (Schmitt et al., 2009; Sternberg, 2008). Assessing students’ academic preparedness is part of determining whether students are ready for college-level or developmental (i.e., noncredit or for-credit below college level) courses.

This qualitative phenomenological study explored students’ lived experiences at Northern New Mexico College (NNMC) to understand the ways that noncognitive factors influenced their academic preparedness. According to Romero (personal communication, June 2, 2011), the director of Educational Opportunity Center (EOC) at NNMC, entering college students receive the computer placement assessment and support system (COMPASS) assessment to evaluate if they need developmental courses. Academically underprepared college students (e.g., determined by COMPASS) are often lacking traditional cognitive skills like reading, writing, or the ability to do math at the college level (Boylan, 2009), and may also lack noncognitive skills (Araujo, Gottlieb, & Moreira, 2007). Romero (personal communication, June 2, 2011) reported because of negative connotations of referring to students as developmental or a remedial student, the name underprepared is a sufficient terminology in referring to students needing developmental non-credit or for-credit courses.

Boylan (2009) noted noncognitive factors added to cognitive factors for assessment can provide a mechanism for targeted interventions in helping the academically underprepared (i.e., students needing below college level courses as determined by COMPASS). In this study, the operationalization of academic underpreparedness was based on whether a student had taken below college level courses to prepare for college level coursework. Academic underprepared students may face obstacles in many noncognitive areas, including the area of personal factors. Researchers at The Annie E. Casey Foundation found that many personal factors can contribute to academic underpreparedness including: (a) a missing parent, (b) transportation issues, (c) parental unemployment, (d) lack of health insurance, (e) and illiterate parents (Griffin, 2008). For this study, noncognitive factors included four areas: (a) personal factors (Griffin, 2008), (b) affective factors (Boylan, 2008b), (c) noncognitive skill factors (Sternberg, 2008), and (d) early educational factors (Fewell & Deutscher, 2004).

By focusing on these four noncognitive areas, the current research explored shared lived experiences related to the influence of noncognitive factors on college student’s academic preparedness. Vygotsky’s developmental law provided a framework for the study. When intelligence quotient (IQ) was thought to be unchanging, Vygotsky (1978) proposed intelligence is dynamic, influenced by noncognitive social-cultural experiences with the ability to imitate a more knowledgeable adult or peer as the measure of intelligence. Chapter 1 includes a background on noncognitive and cognitive factors including the problem, purpose, and significance to the problem with nature of study, the central question including the conceptual framework for the research. The chapter also includes a discussion of the assumptions, limitations, delimitations, and a summary.

Background of the Problem

The history relative to the problem and underprepared students within the U.S. dates back to Harvard giving extra help to students studying for the ministry in Greek and Latin (Mulvey, 2008). Doninger (2009) reported that in 1636 courses were created just 16 years after the landing on Plymouth Rock to help underprepared college students at Harvard. In the 1800s, the University of Wisconsin provided high-school level coursework to college students (Mulvey, 2008). During that same 1800s period, Mulvey noted universities were admitting many academically underprepared college students and were teaching them elementary school coursework and high-school coursework. In brief, academic underpreparedness always has been part of U.S. public higher-education (Doninger, 2009).

However, Moss and Yeaton (2006) noted the increase in underprepared college students was substantially higher because the implementation of open-access policies. Doninger (2009) reported the Higher Education Act (HEA), passed in 1965, reflected an American belief that everyone should have the opportunity for higher education. According to Bankston (2011), open-access policies allowed interest-free loans, part-time jobs, and need-based scholarships to encourage academically underprepared students to enter college. Open-access means to have accessibility to education regardless of students’ academic underpreparedness (Mulvey, 2008; Salas, Portes, D'Amico, & Rios-Aguilar, 2011).

Doninger (2009) suggested a long-standing controversy exists in education about whether academic integrity and open-access policies can coexist. Sternberg and Coffin (2010) demonstrated that maintaining high-standards (i.e., based on academic preparedness standards) at a college was possible while introducing unconventional admissions strategies that allowed the admittance of diverse gender and ethnic populations. Additionally, Sternberg (2009) discovered creative skills (i.e., generating ideas) and practical skills (i.e., implementing ideas), when combined with standardize tests can increase the assessment accuracy of students’ academic preparedness by as much as twice over standardized testing alone. Sternberg and Coffin (2010) noted the Kaleidoscope study at Tufts University used noncognitive factors (i.e., a creative & practical skills rubric) with standardized test scores along with students’ high-school grades (i.e., grade point average or GPA) for admissions testing.

However, the overall design of public higher education has not changed much since the 1983 Nation at Risk report and the accountability movement (Reigeluth & Duffy, 2007). Boylan (2008a) noted neither the new population of students entering college nor college institutions is prepared for the educational challenges resulting from greater higher education access. Further, increasing standardized testing thresholds for college admission may reduce the enrollment potential of diverse ethnic groups while a holistic assessment may increase the applicant pool (Crisp, Horn, Dizinno, & Wang, 2010).

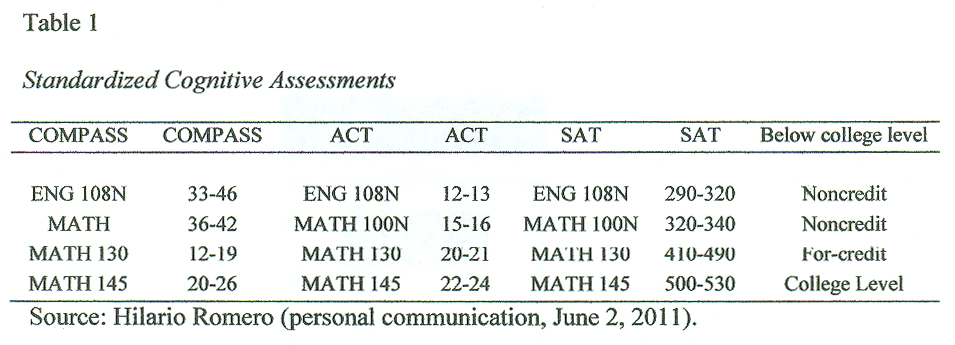

While this study does not focus on selective colleges, it was relevant to note that community colleges use a similar cognitive standardized test derived from COMPASS scores to determine students’ academic preparedness. Just below in Table 1, the equivalence scores between COMPASS and two other cognitive assessments provided an indication of the similarities of standardized cognitive assessments. Boylan (2009) noted that many community colleges as well as universities use COMPASS for developmental placement.

Fike and Fike (2008) reported two million underprepared students may not stay in college without receiving developmental education; their success is contingent on building both noncognitive and cognitive skills. Boylan (2008b) argued that collecting more information on underprepared students may help developmental education design a comprehensive strategy aimed at these students. Boylan (2009) suggested that the triangulation of cognitive and noncognitive indicators (i.e., personal and affective factors) may help to provide developmental education with an accurate assessment of students’ academic preparedness. Noncognitive indicators are increasingly capturing the attention of developmental education and researchers, as these factors are associated with students’ academic preparedness (Schmitt et al., 2009; Sternberg, 2008).

The implication is that investing in building noncognitive skills produces a better return on investment than solely investing in building cognitive skills for adolescents and adults (Cunha & Heckman, 2009). Presently, the placement assessment for students entering college consists of a cognitive test (i.e., Scholastic Aptitude Test also known as SAT) for testing basic skills on which this test determines students’ academic preparedness (Mulvey, 2008). Cognitive tests focus on basic skills like reading, writing, and math (Mathews, 2010), and provide a combined score.

Boylan (2009) implied this combined score may be efficient, but it is not effective for delivering targeted interventions. Boylan also found that most colleges are using SAT or American College Test (ACT) scores to measure basic cognitive skills in the assessment of students’ academic preparedness. According to Syverson (2007), colleges began using SAT test scores in 1926 and ACT test scores in 1959. Syverson showed that the cognitive factors measured by SAT and ACT test scores can assess the academic preparedness of prospective students entering college. This cognitive testing is also an accurate assessment of future dropout rates (Burlison, Murphy, & Dwyer, 2009).

Contrary to these reports, Geiser (2009) reported that under more scrutiny, cognitive testing did not always provide an accurate assessment of students entering college, particularly when assessing academically underprepared students. Empirical evidence suggested that by adding the measurement of noncognitive factors to cognitive test scores may increase the assessment accuracy of these students’ academic preparedness (Araujo et al., 2007; Schmitt et al., 2009; Sternberg, 2008, 2009). According to Heckman (2008), equally important as cognitive skills are noncognitive skills such as: personality, motivation, regulation of emotions (i.e., self regulation), and working with others. Heckman (2008) warned the influence of noncognitive factors in public higher education should not be underrated.

Statement of the Problem

Kaufman (2010) noted public higher education assessments in use do not reflect the full potential of underprepared students and recommended that noncognitive measures become part of college preparedness assessment. Standardize assessments presently in use for assessing college preparedness emphasize cognitive skills, such as: math, English, and reading (Engstrom & Tinto, 2008; Sternberg, 2009). Further, many academically underprepared college students were lacking both noncognitive as well as cognitive skills (Araujo et al., 2007; Boylan, 2009). Geiser (2009) and Kaufman (2010) both acknowledged the validity of standardized assessments but questioned whether these assessments are adequate for understanding every student such as the academic underprepared student.

Adams (2009) argued one such noncognitive factor such as self-efficacy (i.e., a belief in one’s own ability) as an enhancement of motivation is essential for college preparedness. In brief, many underprepared students do not know they are not prepared for college as they often receive academic scholarships but find they need developmental noncredit courses when starting college (Moore, 2007). According to Moore, academically underprepared college students were far more influenced by course engagement and classroom attendance (i.e., motivation-based behaviors) than academic aptitude (i.e., based on SAT) in measuring their academic preparedness. Adams (2009) referred to these underprepared students as riding a roller coaster of emotional experiences affecting self-efficacy and motivation.

The Moore (2007) and Adams (2009) studies are excellent indicators of the importance of noncognitive factors on academic preparedness of students but have limitations in their singular scope on respectively motivation-based behaviors and self-efficacy. The current study expanded the scope of inquiry into four noncognitive areas, which included affective (i.e., motivation and self-efficacy), personal (e.g., at-risk factors) and early education (i.e., preK-12 through K-12), and noncognitive skills (i.e., creative and practical skills). Expanding the scope of inquiry into many noncognitive areas that group noncognitive factors may give a more effective assessment of underprepared college students’ preparedness than a single noncognitive factor. Weel (2008) noted “no single factor has emerged in the psychological literature and it is unlikely that one will be found” (p. 729). The issue is many noncognitive factors are affecting cognitive competencies and devising tests to measure students’ preparedness are difficult (Weel, 2008).

The general problem is that although standardized assessments are efficient, they do not provide an accurate assessment of academic underprepared students (Boylan, 2009). Moore (2007) noted that high-performing underprepared college students in developmental education have a variety of noncognitive factors positively affecting their academic preparedness such as: self-efficacy, effort regulation, and willingness to work hard. The implication for higher education institutions is for admissions officers to develop profiles that emphasize not only cognitive abilities but also noncognitive abilities associated with academic preparedness (Moore, 2007). According to Boylan (2009), self-efficacy, effort regulation, and willingness to work hard are one noncognitive area named affective factors. In this study, an exploration of students’ academic underpreparedness using four areas of noncognitive factors was to expand on earlier investigations.

The specific problem is that only 7% of community colleges in the U.S. use noncognitive factors in assessing the academic preparedness of students (Boylan, 2009). Bailey (2009) noted “developmental education as it is now practiced is not very effective in overcoming academic weaknesses” (p. 12). Without an accurate assessment in community college of a students’ preparedness, it is impossible to design a targeted intervention to help these students (Boylan, 2009). The Boylan (2009) study is arguably the first research to expand the assessment criterion using two noncognitive areas such as affective factors and personal factors. However, this current study expanded Boylan’s study as well as four other studies mentioned previously to obtain a deeper understanding of ways noncognitive factors may influence community college students’ academic preparedness in the open-access situation.

In 2009, the McKinsey study, focusing on the unacceptable condition of education in the U.S., monetized the potential loss in future tax revenue based on educational outcomes between ethnic groups of students (Huffman, 2009). According to Huffman, the research findings on student underpreparedness are momentous because it has implications in associated lost tax revenues for the U.S. estimated at $400 to $670 billion annually. The study also showed a potential loss in the trillions of dollars when comparing the U.S. educational system to educational systems in top performing countries such as Finland and Singapore (Huffman). To understand the phenomenon of academic underpreparedness, this qualitative phenomenological study explored the influence of noncognitive factors on academically underprepared college students at NNMC. NNMC is a 4-year college that maintains a community college mission with open enrollment, and newly enrolling students are tested for their academic preparedness by using COMPASS.

Study Purpose

The purpose of the study was to discover through the exploration of lived experiences, the influence of noncognitive factors on college students’ academic preparedness. By understanding the ways noncognitive factors influence academic preparedness, developmental leadership may better understand academic underpreparedness and understand ways to develop targeted interventions with improved assessments. The use of phenomenology as a research design allowed an exploration to discover through lived experiences the influence of noncognitive factors on students’ academic preparedness. Phenomenology is appropriate for exploring lived experiences (Scroggins, 2010).

Qualitative research is appropriate for exploring what Majer (2009) called individuals’ perceptions, as human actions are often the result of perceptions. Joyner (2009) described variables as inappropriate for qualitative research. However, thematic constructs may allow exploring the ambiguous, which may provide descriptive detail and a deeper understanding through thematic analysis (Creswell, 2007).

In this phenomenological investigation, the research was an exploration of participants’ experiences to find what Hamill and Sinclair (2010) called “the essence of their description” (p. 23). Russell and Aquino-Russell (2010) noted phenomenology is an efficient way of discovering and uncovering a deeper meaning from prior experience of participants experiencing the phenomenon. Participants included 16 academically underprepared students, who seek higher education at NNMC, located in the North Central region of New Mexico.

Significance of the Study

The study has significance because the influence of noncognitive factors on academically underprepared college students may arguably be at the heart of academic preparedness for this subpopulation of college students. Most research on noncognitive factors influence on students’ academic preparedness has a focus on one noncognitive factor such as apathy, motivation, and perseverance, to name a few. However, an attempt to understand students’ academic preparedness from the perspective of many noncognitive factors to discover a deeper understanding of the phenomenon was the aim of this study.

Significance of the Study to the Problem

Significance of the study to the problem. The exploration of noncognitive factors may provide a variety of viewpoints in which the participants’ experienced the combined phenomenon (Creswell, 2007). Boylan (2009) showed that an assessment that includes both noncognitive and cognitive factors provides essential data to improve targeted interventions. In addition, Sternberg (2008) reported that including noncognitive abilities such as creative and practical skills with standardize assessment can increase the gender and ethnic diversity of entrants without lowering academic preparedness standards. Gottfredson and Saklofske (2009) suggested the trend in public education is to find ways that human development and standardize assessment can coincide. The current study was significant to the problem because adding to the knowledge base may result in community colleges using noncognitive factors as well as cognitive factors in assessing academic underprepared college students.

Empirical evidence is beginning to show the importance of noncognitive factors relative to the standardize assessment. Many students who under-perform on the SAT have successful personality traits such as high motivation; other students over-perform on the SAT and still they drop out, which may show a lack of motivation (Borghans, Meijers, & Weel, 2008). Empirical evidence suggested that high school dropouts who pass the general education diploma (GED) examination are cognitively equivalent to high school graduates; however, high school dropouts may lack noncognitive skill sets (Araujo et al., 2007). According to Heckman (2008), empirical evidence suggested that cognitive skill training with the adolescent and adult shows more improvement by focusing on improving noncognitive skills than cognitive skills alone.

Research conducted by Cunha and Heckman (2009) showed that the later cognitive training occurs with basic skills, the less effective it is for the adolescent or adult. This research study is significant because interventions with noncognitive skills and noncognitive personal factors can cause more improvement in adults than cognitive training alone (Cunha & Heckman, 2009). More research is necessary to understand the influence of noncognitive factors on academic underprepared college students.

Significance of the Study to Leadership

Educational professionals are asking for more research for implementing new programs, based on research findings, which address the educational achievement crisis (Sternberg, Kaplan, & Borck, 2007). The study results may help provide educational leaders with a better understanding of underpreparedness through the lived experiences of students to modify developmental programs. Hand and Payne (2008) noted students who feel supported were more likely to continue pursuing their academic goals. By focusing on students’ noncognitive abilities and their cognitive abilities, community college leadership in developmental education can show students that they have the full support of the institution.

To offer this type of support, developmental education leadership may need to understand the ways that noncognitive factors influence students’ academic preparedness. Cognitive skills testing are at the heart of an attempt to provide educational opportunities in the U.S. for every individual (Jackson, 2007). However, Lindqvist and Vestman (2011) noted that diverse gender and ethnic populations of students may benefit more by focusing on their noncognitive skills rather than on their cognitive skills. Exploring the ways noncognitive factors may shape cognitive skills is significant to community college leadership, for developing assessments and support systems that better help students’ academic preparation.

Educational professionals are asking for more research for implementing new programs, based on research findings, which address the educational achievement crisis (Sternberg, Kaplan, & Borck, 2007). The study results may help provide educational leaders with a better understanding of underpreparedness through the lived experiences of students to modify developmental programs. Hand and Payne (2008) noted students who feel supported were more likely to continue pursuing their academic goals. By focusing on students’ noncognitive abilities and their cognitive abilities, community college leadership in developmental education can show students that they have the full support of the institution.

Nature of the Study

In this phenomenological research study, an attempt was made to discover and understand ways noncognitive factors have influenced college students’ academic preparedness. Research participants included 16 students from NNMC. Tape recorder and open-ended interviews provided relevant data that was analyzed thematically with integrated aspects of interpretive phenomelogical analysis (IPA) described by Pringle, Drummond, McLafferty, and Hendry (2011a), which allows phenomenological methods to fit the research study. By integrating aspects of IPA into the structural themes, a modified combination of Giorgi’s (1985) and Moustakas’s (1994) phenomenological methods were vital for discovering the essence of college students’ academic underpreparedness. Additionally, noncognitive factors such as personal factors, affective factors, noncognitive skill factors, and early educational factors were vital in forming the interview questions to explore students’ social-cultural lived experiences.

Early educational factors include the students’ pre-kindergarten educational experiences (Fewell & Deutscher, 2004) and throughout their high school education (Mathews, 2010). The child’s communicative and emotional abilities expanded through speech and modified through social norms provide the ability to overcome impulsive emotions, to execute a plan, and to control their own behavior (Vygotsky, 1978). In brief, as adults label actions verbally, children may repeat the label, which eventually produces higher mental processes (Van Der Veer, 2007). Understanding early education experiences through a phenomenological exploration may reveal one aspect of the influence of noncognitive factors on college students’ academic preparedness but several other aspects may also have a significant influence.

Sternberg (2008) discovered through research studies that noncognitive skill factors such as creativity and practical skills were just as important to academic preparedness of students as analytical skills. His studies have shown that teaching to match students’ natural abilities may allow these students to outperform other students not educated to match their natural abilities (Sternberg, 2008). In addition to this noncognitive area, other noncognitive areas explored in this study included affective factors and personal factors.

Boylan (2009) defined affective factors as: students’ attitude toward learning, willingness to make an extra effort, and willingness to seek help. Griffin (2008) described personal factors as a missing parent, parental unemployment, and having an illiterate parent. This exploratory study provided a comprehensive view of the many ways noncognitive factors may influence students’ academic preparedness by exploring these previously mentioned four noncognitive areas.

Overview of the Research Method

Qualitative research is an exploratory approach to analyze the phenomenon (Creswell, 2007). According to Goretskaya (2006), the qualitative method is appropriate because it allows participants to discuss their learning experiences with descriptions and interpretations. Barbatis (2008) reported that a hallmark of using the qualitative method of analysis is the ability to explore real-world situations through open-ended questions, without predetermined constraints. According to Farakish (2008), qualitative research becomes a reference for future studies, as opposed to the ultimate conclusion.

Qualitative research empowers individuals by allowing them to share their personal stories while permitting an understanding of complex social issues (Creswell, 2007). Goretskaya (2006) noted that the study of lived experiences is not permitted in quantitative research. The quantitative method is a way to examine causal relationships between variables, and it is not suitable for exploratory research (Joyner, 2009). The quantitative method is not appropriate for a deeper understanding of social phenomenon such as lived experiences of academically underprepared college students to explore ways noncognitive factors may influence their academic preparedness. A growing number of research professionals share a belief that qualitative methods provide perceptive knowledge of human phenomena more than from quantitative methods only (Williams & Gunter, 2006).

McClelland (2008) noted that qualitative research can make possible an inquiry into the minds of individuals within a community. According to Sternberg (2007b), a valid starting point is the influences that affect different views on what constitutes valuable learning. Qualitative phenomenological research was more appropriate for exploring students’ lived experiences, personal circumstances, and the learning environment experienced by students in context to Vygotsky’s notion of culturally-mediated higher mental functions, also referred to as developmental law (Vygotsky, 1978). This developmental law is a transmission of skills with guidance from a more capable peer or adult into a potential future independent capability of problem solving demonstrated by the students’ ability to imitate (Vygotsky). Phenomenology provides a qualitative design in which the primary focus is on the lived experiences of the individual and allows for an inquiry into their minds (McClelland, 2008).

Overview of the Design Appropriateness

For this study, the research design had an integrated interpretive phenomenological analysis, interpreted by Pringle et al. (2011a), as having a combination of interpretive and descriptive elements in establishing convergent perspective, divergent perspective, and shared commonalities. Commonalities shared across lived experiences can formulate into insights that arguably contribute toward theory; not theory with a capital-T but a lower-case t (Pringle et al., 2011a). According to Pringle et al. (2011a), when theoretical transferability, as opposed to empirical generalizing, is part of conceptualizing to a wider contribution; it is arguably making a contribution toward theory. As well, Weel (2008) noted the lack of theory related to noncognitive factors. The study contributes to the research literature, which may contribute to a general theory of noncognitive factors in the future.

Creswell (2007) noted phenomenology is one of several research designs in qualitative research that includes: case studies, ethnography, and grounded theory for examples of only a few. The phenomenological design provides a mechanism, in this study, for exploring the mind in reference to individuals’ culturally lived experiences associated with noncognitive factors. As reported by Creswell (2007), qualitative research can appropriately combine with the phenomenological design, as the phenomenological approach is appropriate for collecting data from lived experiences.

Standing (2009) postulated phenomenology research design is relevant because of the personal interpretation derived from lived experiences, as opposed to empirical generalizing. Flood (2010) noted that phenomenology has extensive independence from ethnography with a focus on inner subjectivity. This study did not require active participation or observation used in ethnographic studies; therefore, the phenomenological design was more appropriate than the ethnographic design.

In another distinction of design appropriateness, qualitative data from a grounded theory research design includes hypotheses grounded within the collected data (Williams & Gunter, 2006). Creswell (2007) reported that grounded theory may use concepts from the collected data to build a resultant theory during the research process. In contrast, the phenomenological research design is not concerned with developing theory, instead, it is more of a reduction of the individual’s consciousness to reflect the phenomenon through perceptions; thereby, finding meaning in the shared experience (Creswell, 2007; O'Murchadha, 2008). This study did not need a theory as the study was merely an attempt to establish meaning through participants’ shared experiences.

In another example of design appropriateness, Rescigno (2009) noted that the case study allows analysis of the whole to see how the pieces fit together. The approach helps to explain the reasons behind a problem. However, in phenomenological research, Flood (2010) reported finding meaning is the main concern, not to solve a problem. Because the research did not involve problem solving, the phenomenological research design was more appropriate than the case study. These distinctions between qualitative designs were a necessary discussion in shaping the goal and research questions for the study.

Central Research Question and Sub-Questions

Mayer (2008) suggested that the research questions should have a theoretical grounding with educational implications to advance the field in addressing practical issues which may lead to improve learning. The noncognitive areas that may influence college students’ academic preparedness are: (a) personal factors, (b) affective factors, (c) noncognitive skill factors, and (d) early educational factors. Shown just below, Figure 1 is a compilation from three journal articles and two doctoral dissertations created to guide the study.

The challenge is to find a way to disclose the complexity hidden within what seems to be simple (Brough, 2008). Creswell (2007) recommended starting the investigation by using the central research question in the broadest way possible. Using this recommendation, the noncognitive areas in Figure 1 support the central research question: In what ways do noncognitive factors influence lived experience relating to preparedness of academically underprepared students at Northern New Mexico College?

In this study, the central question was an effort to address the study’s purpose to discover through the exploration of lived experiences, the influence of noncognitive factors on students’ academic preparedness. To reveal the essence and meaning behind college students’ academic underpreparedness, five research sub-questions helped to guide this phenomenological study:

R1. How do academically underprepared college students perceive their college lived experience?

R2. How do academically underprepared college students perceive their lived experience related to early educational factors before and during k-12?

R3. How do academically underprepared students in college describe lived experience related to personal factors that may help or hinder their educational experiences?

R4. In what ways do academically underprepared college students describe lived experience related to affective factors such as overcoming the challenges they face in obtaining a college degree?

R5. What influences do creativity and practical skills have on participants’ lived experience related to their academic preparedness?

These five research sub-questions provided guidance in discovering the influence of noncognitive factors on academic underpreparedness of college students using their perceptions, which ultimately connected to the theoretical framework.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework encompassed students developing higher brain functions through social-cultural experiences that precedes their independent achievement by imitation of a more knowledgeable adult or peer as a learning developmental law (Vygotsky, 1978). Vygotsky stipulated that this social-culturally formulated developmental law integrates with behavioral development in which students subordinate their behavior externally through group interactions and later develop an internal self-regulation of their behavior on which allows for future planning. Sanagavarapu (2008) implied an individuals’ self-regulation on which metacognitive skills such as planning may develop into problem solving skills was a social cultural phenomenon primarily emanating from an individuals’ home environment.

According to Creswell (2007), the theoretical framework of a research study can involve the historic context of the problem. The historical context is that cognitive testing used for assessing college preparedness of students does not provide an accurate assessment of academically underprepared students (Moore, 2007; Schmitt et al., 2009; Sternberg, 2008). This involves human cognitive development beginning with social interaction before the individual internalizes knowledge (Eun, 2008). Research on the executive control system within the prefrontal cortex has indicated that cognitive inhibitory control (i.e., cognition and metacognition) and behavioral inhibitory control (i.e., self-regulation) are distinct functions within the same inhibitory area (Bierman, Nix, Greenberg, Blair, & Domitrovich, 2008). According to Bierman et al. (2008), their study suggested a neurobiological foundation to academic preparedness and that cognitive ability may become enhanced by learning to control noncognitive behaviors.

Gardner (2006) reported a limited portion of human potential (i.e., logical-mathematical intelligence) is assessed with the traditional SAT IQ test. Shavinina (2008) argued IQ test only measure descriptive knowledge, not intelligence nor ability to learn. Boylan (2009) noted more information is necessary to understand students’ academic underpreparedness through noncognitive factors such as personal and affective factors to improve academic assessment accuracy and improve targeted interventions. To understand students’ academic underpreparedness, Vygotsky’s developmental law becomes foundational to this research, which may arguably be primary to educational development relative to students’ self regulation, metacognition, and their cognitive academic underpreparedness.

Definition of Terms

Affective factors: Noncognitive factors relating to determination, attitudes, and willingness to accept help as well as autonomy and willingness to work hard on assignments (Boylan, 2009).

Cognitive factors: These are analytical skills such as reading, writing, and mathematics (Sternberg, 2008).

Developmental education: Support services designed as a comprehensive way to improve attitudes, habits, and skills of students in college (Boylan, 2008b; Boylan & Bonham, 2007).

Developmental law: Individuals develop higher brain functions starting within the social group, with an adult, or through a more knowledgeable peer on which independent achievement occurs through imitation (Vygotsky, 1978).

Early educational factors: This term refers to students’ combined educational background experienced with the mother before kindergarten focusing on maternal responsivity (Fewell & Deutscher, 2004) and through their high-school education (Mathews, 2010).

General factor of intelligence (i.e., g-factor): A statistical factor analysis method used as a common source of variance within IQ testing and standardized cognitive tests, with each source possessing different loadings of g-factor (Kane & Brand, 2008). The notion of fixed intelligence, called general intelligence or g-factor, is the latent variable within standardized cognitive tests (Gardner, 2006; Kanazawa, 2009).

Giorgi’s phenomenology (i.e., one aspect used in this study): Focus on the combining of participants’ or co-researchers’ experiences of a phenomenon with the imagination of the primary researcher by analyzing emotions and perceptions to discover the structure within the experience (Giorgi, 1985).

Imaginative variation: Giorgi (1985) described imaginative variation as considering many viewpoints surrounding descriptions of the phenomenon to understand participant’s perceptions in construing themes, not necessarily from specific text but from participant’s intentions found within the text.

Interpretive phenomenological analysis: A combination of descriptive and interpretive elements but focusing to seek examples of divergent perspectives, convergent perspectives, and commonalities and has flexibility to adapt to the needs of the study (Pringle et al., 2011a).

Invariant constitutes: This is the lowest level of structural hierarchy representing the closest accounts of participants’ experiences (Scroggins, 2010).

Maternal responsivity: The care and communication that occurs between mother and child starting from birth but has a focus on an adult reading to the child (Fewell & Deutscher, 2004).

Metacognition: This is an individuals’ conscious process of regulating their cognition (Efklides, 2008). Efklides described metacognitive skills as cognitive strategies such as planning strategies.

Moustakas’s phenomenology (i.e., one aspect used in this study): A comprehensive depiction of shared experiences through a creative synthesis of participants’ descriptions including personal knowledge (Moustakas, 1994).

Multiple intelligences: Pluralizes the concept of intelligence in which individuals have several intelligences (Gardner, 2006).

Noncognitive skills: This term refers to skills such as practical and creative skills routinely not included in the traditional SAT testing (Sternberg, 2010). These noncognitive skills are a set of skills that integrate analytical, practical, and creative ways of thinking (Sternberg, 2008).

Open-access: This means to have accessibility to education regardless of students’ academic underpreparedness (Mulvey, 2008; Salas et al., 2011).

Personal factors: Personal factors are at risk factors like a missing parent, unemployment, or illiterate parents (Griffin, 2008).

Prepared students: Students who do well on cognitive tests such as: math, reading, and English (Engstrom & Tinto, 2008).

Self-regulation: Self-regulation is a balance between behavioral or emotional control and cognitive regulation for the attainment of personal goals (Blair & Diamond, 2008). Sitzmann and Ely (2011) implied self-regulation was a behavioral choice process of choosing a goal and how much resources to use for attainment of that goal.

Successful intelligence theory: Individuals have strengths and weaknesses in creative, practical, and analytical areas and individuals compensate for any weak areas making them successfully intelligent (Sternberg, 2008).

Underprepared students: This term refers to students lacking in traditional cognitive skills like math, reading, or English (Boylan, 2009); also called academically at-risk students (Henderson, 2009) who lack noncognitive skill sets (Araujo et al., 2007). The operationalization of academic underpreparedness was based on whether a student had taken below college level courses to prepare for college level coursework. According to Romero (personal communication, June 2, 2011), low COMPASS scores identify students as academically underprepared.

Assumptions

The assumption was that the criterion used to choose participants represents underprepared students and; therefore, are not succeeding in school. Another assumption was that noncognitive factors influence students’ academic preparedness. The broad assumption was noncognitive factors are relevant to the choices that underprepared students make because these influences on their choices involve the formulation of meaning (Flood, 2010), which may affect their late forming abilities of self-regulation and metacognition. Because of the voluntary nature of the study, the assumption was also made that these students would respond honestly to interview questions. Creswell (2007) reported that in phenomenology, the assumption is that participants’ lived experiences make enough sense to them for the experience to be expressed.

Scope

The scope within this study involved the participants’ lived experiences and their perceptions relative to four groups of noncognitive factors. This study involved research at NNMC using 16 participants. Permission to use the premises authorized the recruitment of participants and to use the name of the college in the study (see Appendix A). The recruitment of participants occurred using purposive sampling. As the research results were only generalizable to other colleges with similar populations of ethnic diversity, the small sample was not a concern (Joyner, 2009).

Limitations

Flood (2010) noted that phenomenology is a research design focusing on the meaning of lived experience rather than abstract concepts or arguing a point. As well, Mathews (2010) reported that the phenomenological design can become a limitation only when the phenomenon entails an understanding without going deeper. The results of the study generalize only to other colleges that have similar diverse ethnic populations such as academically underprepared college students at NNMC.

Protecting the students’ rights and privacy was part of the research design. The informed consent form included participants’ rights and their privacy written as simply as possible (see Appendix B). A pseudonym used for each participant was a vital part of the research study, and the interview protocol (see Appendix C) guided the interview process. Participants’ names locked in a cabinet were in a safe and after 3 years destroyed. The transcriber of the recorded interviews signed a nondisclosure agreement (see Appendix D) to ensure the protection of participants’ identity.

Delimitations

The study included a purposive sample of 16 students from NNMC in need of academic support in English or mathematics. Participants were at least 19 years in age taking or have taken below college level courses to prepare for college level coursework. Participants’ COMPASS scores were not necessary but merely a verification of students’ eligibility occurred by asking them if they had taken any below college level courses to prepare for college level coursework. The study used a small sample size; however, the small sample size permits a broader exploration (Danko, 2010). No gender or ethnic exclusions were necessary.

Summary

The difference between underprepared students who do not have higher education and prepared students who do have higher education continues to grow (Torraco, 2007). The problem is using only cognitive factors to assess both prepared and underprepared students are not a reliable assessment of academic preparedness for the underprepared students (Moore, 2007; Schmitt et al., 2009; Sternberg, 2008). Boylan (2009) noted that only 7% of colleges use noncognitive factors with cognitive factors to assess academic preparedness for inclusion into developmental coursework. United States educational policy primarily focuses on measuring cognitive skills using standardized tests (Heckman, 2008). According to Boylan (2009), triangulating cognitive factors with noncognitive factors (i.e., affective & personal factors) may provide a more accurate assessment of students’ academic preparedness.

In this study, developmental law was the foundational framework in which social-cultural experiences are the foundation for higher mental functions in the human brain emanating from imitation of a more knowledgeable adult or peer (Vygotsky, 1978). Cunha and Heckman (2009) implied that because of the slow mental maturity of the brain, educational intervention with adults is more efficient and may provide a better ROI through the enhancement of noncognitive skills than cognitive training alone. Using research advances in knowledge about the brain and noncognitive factors, the creation and reproduction of successful programs are necessary, so leadership can reverse the educational crisis through the enhancement of much-needed programs (Sternberg et al., 2007). The research was an exploration into the influence of noncognitive factors on academically underprepared college students, in four distinct noncognitive areas, to discover the meaning of their shared experience.

Chapter 1 included the: (a) problem background, (b) problem, (c) purpose, (d) problem significance, (e) research questions, and (f) conceptual framework for the research. The study also entailed assumptions, limitations, and delimitations as well as a summary to form the basis for this exploratory study. The central research question and research sub-questions were to explore the influence of noncognitive factors on college students’ academic preparedness.

Chapter 2 introduces the phenomenon of academic underpreparedness through a literature review of various topics such as: history of underpreparedness, influence of cognitive and noncognitive factors, developmental education, and Vygotsky’s developmental law. The literature reviewed includes: studies surrounding the research problem, gaps in the literature, and key points relating to the central research question. This chapter includes a discussion of contrasting opinions, an analysis of the review, and a discussion of general key points.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License

Please attribute legal copies of this work to Moire Tomas, Ed.D.

Also, some of the work(s) on this site may be separately licensed.

UMI Number: 3536193

Published by ProQuest LLC (2013)